The eye test for ophthalmic residents

Leigh Spielberg

Published: Wednesday, May 1, 2013

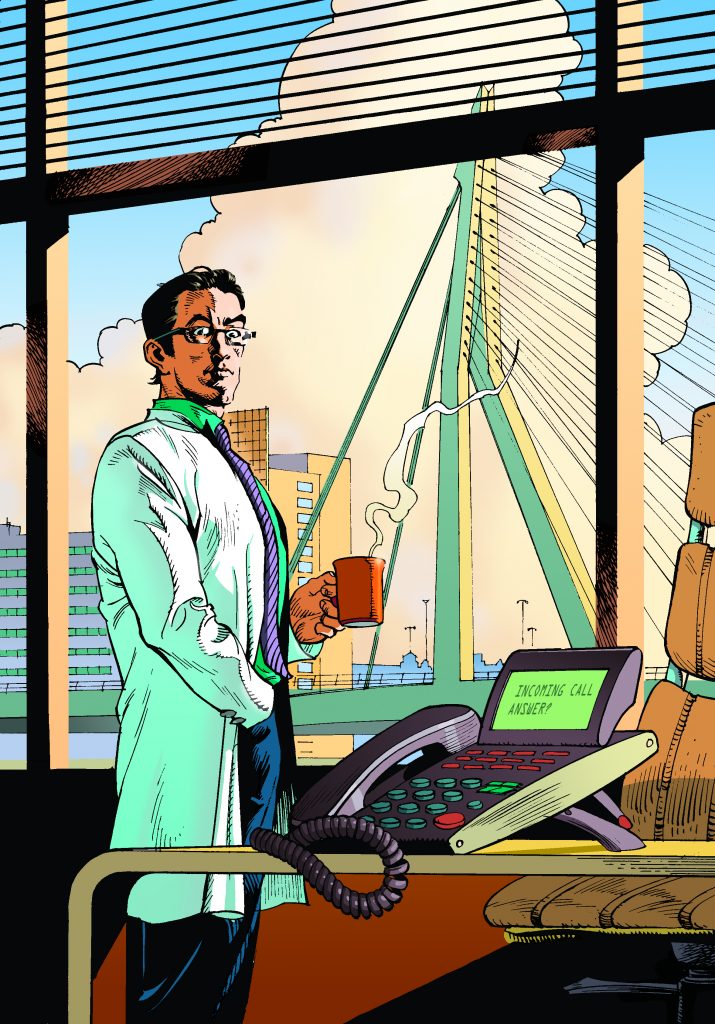

The Residents' Lounge in the Rotterdam Eye Hospital usually has a rather carefree vibe. Conversation bounces from discussions of last weekend's activities to the spectacular cases that presented the night before in the emergency room. And the conversation is always interesting. One resident recently married a Brazilian lawyer he met while in Vienna. Another resident (me) just welcomed the arrival of his first child. How's that for early-morning conversation? To be sure, the carefree vibe is punctuated by some requisite whining. After all, it's raining outside, the sun has yet to rise and the caffeine has yet to reach our blood streams, but we're generally pretty happy to be there in the morning and to get started early.

A few weeks ago, we 20 residents arrived in the clinic just before 8am, as we always do. One or two arrived by train, two or three on foot and, this being Holland, the rest by bicycle. We swarmed into the Residents’ Lounge and gathered around the espresso machine. But on this particular day, the mood was different. We were all tense, agitated, excited, like greyhounds at the starting gate. There, above the espresso machine's distinctive droning hum, we looked at each other and hoped it would be relatively painless and over soon.

The yearly ophthalmology exams were about to begin and the pressure was on. The exam proctor entered to tell us it was time to start. We filed out of the Residents' Lounge and into the hospital's conference room. At 8 o'clock sharp, the exams were distributed and we were off.

All ophthalmology residents throughout The Netherlands take these exams simultaneously, and passing four sets of them is required before graduation. This year was my first time, and I realised that they were the first exams that I'd ever taken in which the material would be relevant for the rest of my career. Sure, information that I had studied in medical school has been secondarily useful during my ophthalmology residency. Medical retina is impossible to practise without understanding diabetes as a systemic disease. But I found myself, a year into my residency, studying the actual presentations of uveitis, the diagnostics of glaucoma and the techniques of cataract surgery, the updated versions of which I'll still be applying 30 years from now.

No longer did I have the medical school feeling of, I'm going to try to learn this really well so I'll get good enough grades to be able to get into ophthalmology and actually learn what I want to learn. This was it! Learn it and remember it! Make it a part of yourself.

The Residents' Lounge in the Rotterdam Eye Hospital usually has a rather carefree vibe. Conversation bounces from discussions of last weekend's activities to the spectacular cases that presented the night before in the emergency room. And the conversation is always interesting. One resident recently married a Brazilian lawyer he met while in Vienna. Another resident (me) just welcomed the arrival of his first child. How's that for early-morning conversation? To be sure, the carefree vibe is punctuated by some requisite whining. After all, it's raining outside, the sun has yet to rise and the caffeine has yet to reach our blood streams, but we're generally pretty happy to be there in the morning and to get started early.

A few weeks ago, we 20 residents arrived in the clinic just before 8am, as we always do. One or two arrived by train, two or three on foot and, this being Holland, the rest by bicycle. We swarmed into the Residents’ Lounge and gathered around the espresso machine. But on this particular day, the mood was different. We were all tense, agitated, excited, like greyhounds at the starting gate. There, above the espresso machine's distinctive droning hum, we looked at each other and hoped it would be relatively painless and over soon.

The yearly ophthalmology exams were about to begin and the pressure was on. The exam proctor entered to tell us it was time to start. We filed out of the Residents' Lounge and into the hospital's conference room. At 8 o'clock sharp, the exams were distributed and we were off.

All ophthalmology residents throughout The Netherlands take these exams simultaneously, and passing four sets of them is required before graduation. This year was my first time, and I realised that they were the first exams that I'd ever taken in which the material would be relevant for the rest of my career. Sure, information that I had studied in medical school has been secondarily useful during my ophthalmology residency. Medical retina is impossible to practise without understanding diabetes as a systemic disease. But I found myself, a year into my residency, studying the actual presentations of uveitis, the diagnostics of glaucoma and the techniques of cataract surgery, the updated versions of which I'll still be applying 30 years from now.

No longer did I have the medical school feeling of, I'm going to try to learn this really well so I'll get good enough grades to be able to get into ophthalmology and actually learn what I want to learn. This was it! Learn it and remember it! Make it a part of yourself.