Cataract, OSD

Coming to Grips with OSD in Cataract Patients

Helping patients own their condition minimises dissatisfaction. Dermot McGrath reports from Milan.

Dermot McGrath

Published: Wednesday, November 9, 2022

Ocular surface disease (OSD) is a major cause of suboptimal cataract surgery outcomes, but having a clear strategy and ensuring careful preoperative screening to detect potential issues can help to avoid many of the pitfalls associated with OSD in cataract patients, according to Allan R Slomovic MD.

“OSD is very prevalent in the cataract patient population,” Prof Slomovic said. “Remember, these are elderly patients [who] are often on numerous medications—especially anti-glaucoma medications—which can affect the ocular surface. Moreover, OSD can significantly affect keratometry and biometry, leading to refractive postoperative surprises and patient dissatisfaction following cataract surgery.”

The best approach, he said, is to perform a staged procedure, taking care first of the ocular surface disease and waiting six to eight weeks before repeating biometry and topography prior to cataract removal.

Prof Slomovic focused on three principal ocular surface problems: pterygium, epithelial basement membrane dystrophy (EBMD), and dry eye disease (DED).

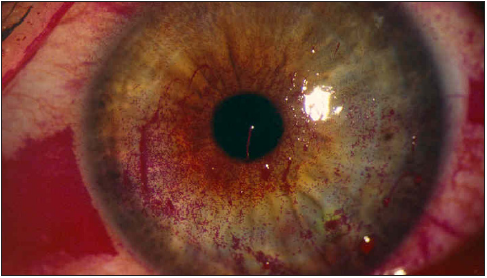

To effectively deal with a patient presenting with both pterygium and cataract, it is critical to understand the effects pterygium has on corneal topography. “It causes flattening of the cornea in the area of the pterygium [and] results in irregular with-the-rule astigmatism and an increase in higher-order aberrations,” he said.

Prof Slomovic advised first removing the pterygium with a conjunctival autograft, then waiting six to eight weeks to obtain stable keratometry and topography. Once achieved, the surgeon can proceed with biometry and phacoemulsification to remove the cataract.

“We looked at patients treated this way in a previous study, and it showed pterygium surgery successfully reduces the topographic and refractive astigmatism, thereby making biometry more accurate,” he said. “The best-corrected visual acuity also improved, and pterygium excision reduced higher-order aberrations caused by the pterygium.”

Anterior basement membrane dystrophy is the most common corneal dystrophy and is especially significant if the changes manifest in the visual axis, Prof Slomovic explained.

He presented the case of a 75-year-old male with declining visual acuity referred for consideration of cataract surgery. The patient had two central Salzmann nodules and irregular astigmatism. Six weeks after superficial keratectomy to remove the nodules, the best-corrected visual acuity recovered to 20/25, avoiding cataract surgery.

For cases of DED, Prof Slomovic emphasised the importance of addressing the problem preoperatively.

“DED can cause corneal staining and abnormalities in keratometry, topography, and biometry,” he said. “Dry eye treatment leads to changes in IOL power calculations and postoperative refractive outcomes. Therefore, assessing and treating patients for dry eyes prior to cataract surgery is important in maximising refractive outcomes.”

Prof Slomovic stressed that the ophthalmologist’s role is to optimise the ocular surface before and after surgery and set realistic expectations by explaining to the patient how they have two separate conditions needing treatment.

“If you tell the patient about their ocular surface disease before the surgery, they own it,” he said. “However, if they only become aware of it after the cataract surgery, they will presume the surgeon caused the problem.”

Particular vigilance is needed in the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the presence of DED, as it can lead to corneal melts and perforation, Prof Slomovic warned.

“We now have seven studies in the scientific literature reporting the association of NSAIDs and corneal melts in the setting of cataract surgery,” he said.

Allan R Slomovic MD is professor of ophthalmology at the University of Toronto, Canada. allan.slomovic@utoronto.ca

Tags: 40th Congress of the ESCRS

Latest Articles

Towards a Unified IOL Classification

The new IOL functional classification needs a strong and unified effort from surgeons, societies, and industry.

The 5 Ws of Post-Presbyopic IOL Enhancement

Fine-tuning refractive outcomes to meet patient expectations.

AI Shows Promise for Meibography Grading

Study demonstrates accuracy in detecting abnormalities and subtle changes in meibomian glands.

Are There Differences Between Male and Female Eyes?

TOGA Session panel underlined the need for more studies on gender differences.

Simulating Laser Vision Correction Outcomes

Individualised planning models could reduce ectasia risk and improve outcomes.

Need to Know: Aberrations, Aberrometry, and Aberropia

Understanding the nomenclature and techniques.

When Is It Time to Remove a Phakic IOL?

Close monitoring of endothelial cell loss in phakic IOL patients and timely explantation may avoid surgical complications.

Delivering Uncompromising Cataract Care

Expert panel considers tips and tricks for cataracts and compromised corneas.

Organising for Success

Professional and personal goals drive practice ownership and operational choices.